Making search engines consistently fast is extremely hard. They have tons of interconnected components, and a minor degradation in one part of the system can easily spiral out of control and become a critical performance issue. Caches in particular are especially crucial to get right, because they can cause a great variety of problems: sub-optimal memory usage, query performance degradations, excessive contention in hot paths, etc. In this post, we’ll cover the current state of caches in the Coveo index, as well as the design and implementation of a new caching library able to solve our issues.

Currently, the Coveo index has around 30 internal caches, each of them using one of six different implementations. Among other things, they cache parts of internal index structures, frequently returned documents, and the results of often-seen query expressions. The purpose of these caches being wildly different from one another, it follows that their implementations are also very heterogeneous. We have, among others, multi-level caches with compressed levels, persisted caches, as well as a lot of Least-Recently-Used (LRU) caches.

LRU is one of the simplest caching schemes available. It offers an acceptable level of performance in most scenarios, while at the same time being really easy to implement.

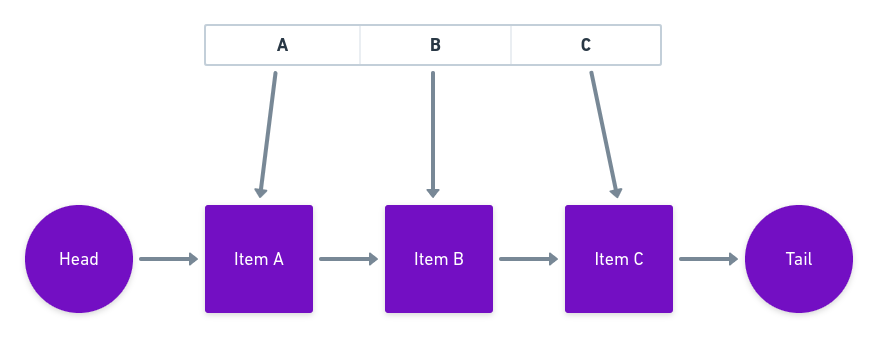

In-Memory Structure of an LRU Cache

In-Memory Structure of an LRU Cache

LRU is usually implemented as a linked list. Whenever an item is added or accessed in the cache, it is moved to the front of the list. When attempting to insert an item while the cache is full, the item at the back of the list is evicted to make some space.

While LRU isn’t bad per se, it does have some issues that make it far from optimal - especially for search workloads.

First, LRU is prone to high churn; items are very often inserted and evicted from the cache. This means that specific query patterns (such as a full scan of the index contents) can exclude potentially expensive values from the cache just because of the ordering of access operations.

Second and perhaps most importantly, LRU makes the bold assumption that all cache misses have an equal cost. This assumption can cause massive issues if, for instance, some items were to take 100x more time to compute than some others - expensive data should have priority in cache.

Although we do have a reusable implementation of LRU in-house, we often end up implementing custom logic on top of it to reduce the fundamental issues this algorithm causes.

The sheer number of different cache implementations in our code base makes it hard to add features (e.g., metrics for tracking hit rate) to all caches, because doing so would introduce significant code duplication. Furthermore, the various implementations don’t uphold the same invariants (e.g., thread safety), so trying to change things across the board can be a bit like dancing on a minefield.

Since these caches were added one at the time over the course of several years, no organized effort has been made to try and unify these implementations while still satisfying all of our existing requirements.

At least, not until now.

Designing a Solution

When we noticed that the performance of our caches wasn’t where we wanted it to be, and that making large changes across many caches was becoming slow and error-prone, we took the initiative to design what has now become a general-purpose C++ caching library called Cachemere.

The first step in designing this new general-purpose cache is to create a modular system for describing cache behavior. Doing so will allow us to implement a generic cache once, and override specific parts of its behavior as required by the use case.

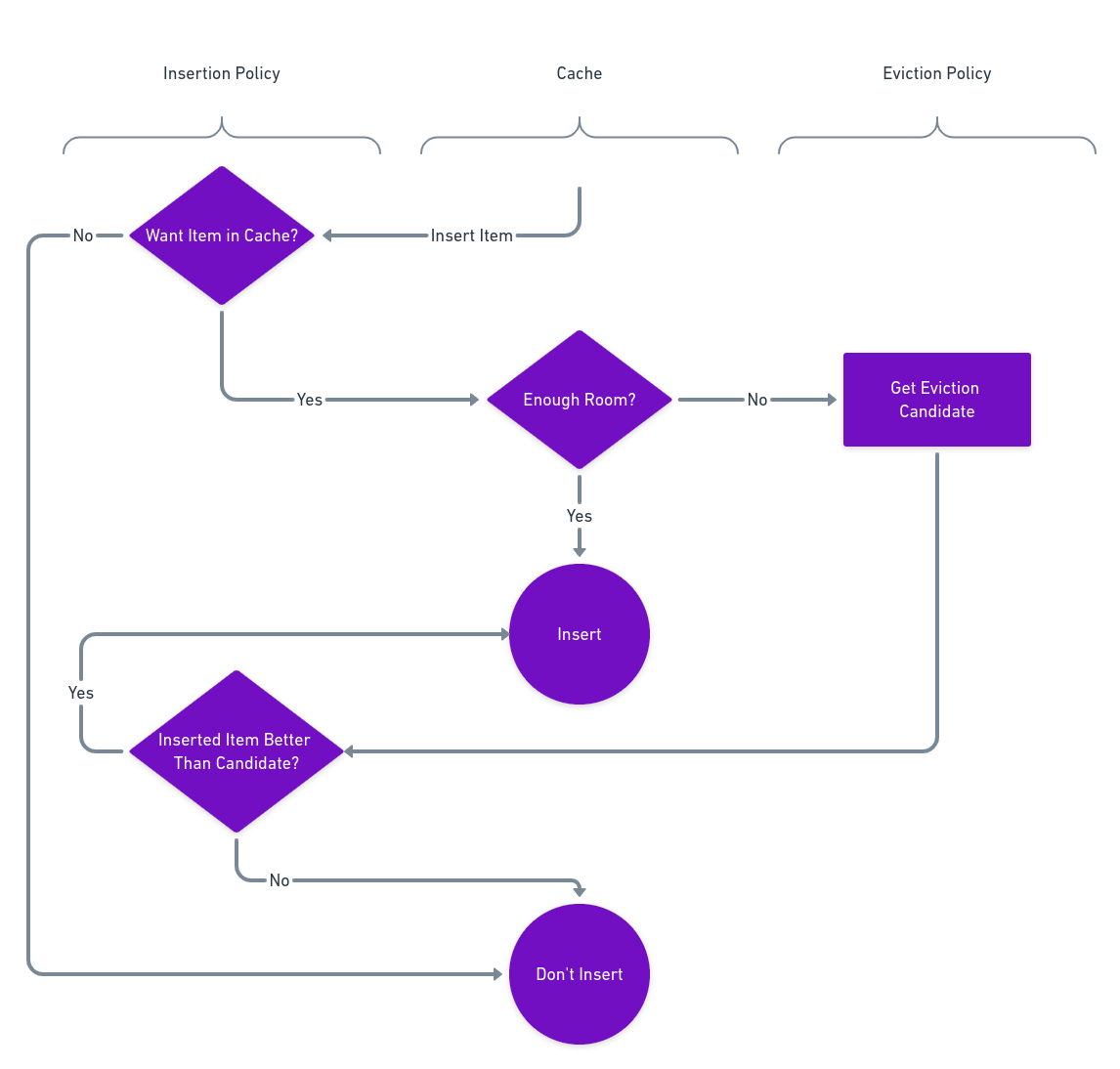

When mapping out the flowchart representing a typical cache insertion process (illustrated below), a logical separation in three components can be observed. This separation is the basis of Cachemere’s design.

The Insertion Policy answers all questions related to whether an item should be in the cache. The Cache owns the values that were inserted and tracks its memory usage. Meanwhile, the Eviction Policy is responsible for ordering items that are in the cache by order of preference.

Cachemere Insertion Process

Cachemere Insertion Process

This design allows Cachemere to provide a variety of policies, while still allowing the end-user to implement purpose-built policies without losing the benefits of a unified cache.

What’s In the Box?

Cachemere provides a configurable cache implementation, which comes with goodies such as automatic tracking of hit rate and byte hit rate.

At the time of writing, Cachemere also comes with a selection of policies used to implement various caching schemes:

Least-Recently-Used (LRU)

Simplest caching scheme. Aims to provide a good baseline.

Tiny Least-Frequently-Used (TinyLFU)

Memory-conscious caching scheme aiming to maximize hit rate.

Read the paper here.

Greedy-Dual-Size-Frequency (GDSF)

Caching scheme aiming to minimize the average cost of a cache miss.

For more information, take a look at the documentation.

Using Cachemere

In addition to all that flexibility, Cachemere is designed to be highly ergonomic. Even though the library supports high levels of customization, it remains very simple to use for common cases thanks to sensible defaults and pre-configured caches provided out of the box.

To illustrate this, let’s build a TinyLFU cache to store instances of ExpensiveObject identified by string keys. We’ll start by including relevant headers and defining our ExpensiveObject.

#include <cassert>

#include <optional>

#include <string>

#include <cachemere.h>

// For the sake of this example, suppose that m_something

// is very expensive to compute :)

struct ExpensiveObject {

int m_something;

};

Now, we’ll define some type aliases to make the role of the different template parameters a bit clearer. This is completely optional but enhances readability.

The cache needs to be configured with two objects for computing the amount of memory used by each key and value. Fortunately, Cachemere provides a suite of measurement tools to cover most common use cases (e.g., calling sizeof(), Object::capacity() , or Object::size()).

// ...

// Our cache will store instances of ExpensiveObject identified by string keys.

using Key = std::string;

using Value = ExpensiveObject;

// Since the key is a string, which have dynamically allocated memory,

// we'll use CapacityDynamicallyAllocated to get an estimate of

// the allocated memory for each key.

using KeySize = cachemere::measurement::CapacityDynamicallyAllocated<std::string>;

// Since ExpensiveObject has no dynamically allocated memory, a simple

// sizeof gives an good estimate of memory usage.

using ValueSize = cachemere::measurement::SizeOf<ExpensiveObject>;

Once we have all our parameters, we can declare the type of our cache. Here we use the TinyLFUCache preset provided by Cachemere, but the same cache can be built by hand by using the InsertionTinyLFU insertion policy along with the EvictionSegmentedLRU eviction policy.

// ...

// Using the preset.

using MyCache = cachemere::presets::TinyLFUCache<Key, Value, ValueSize, KeySize>;

// Building manually.

using MyCache = cachemere::Cache<Key,

Value,

cachemere::policy::InsertionTinyLFU,

cachemere::policy::EvictionSegmentedLRU,

ValueSize,

KeySize>;

Now that we have declared our cache, usage is not very different from other associative containers.

// ...

int main()

{

// Create a new cache with a maximum size of 150kb.

MyCache cache{150 * 1024};

// Lookup an object

std::optional<ExpensiveObject> object = cache.find("some_key");

if (!object.has_value()) {

// Cache miss. Insert and lookup again.

cache.insert("some_key", ExpensiveObject{42});

if (auto my_object = cache.find("some_key")) {

assert(my_object->m_something == 42);

}

}

return 0;

}

Are We Past LRU?

Now that we’ve designed an elegant solution to our caching problems, let’s examine Cachemere’s performance, specifically its accuracy.

As stated above, LRU’s largest shortcomings in our applications are its sub-optimal hit rate, and its tendency to evict items that are very costly to reload when accessed again (leading to much higher average latency due to long reloads).

To measure how well Cachemere’s policies address these shortcomings, we designed a benchmark with characteristics similar to our production workloads: heterogeneous item sizes, heterogeneous reload costs, along with a very small fraction (~0.5% - 1%) of items having a much higher (~100x) reload cost.

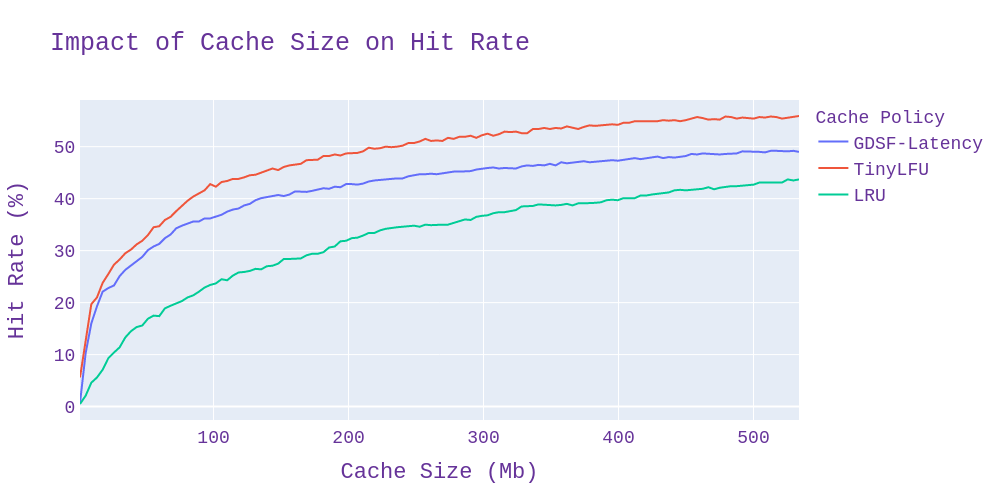

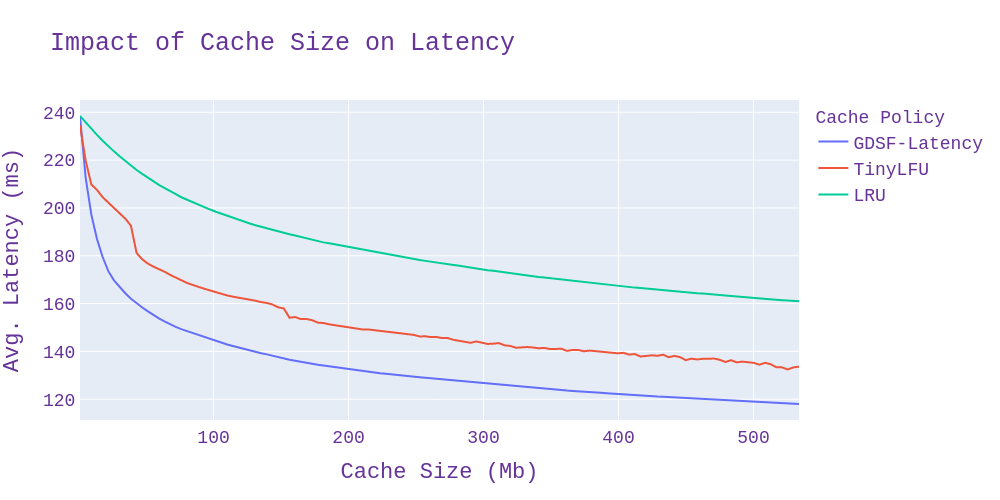

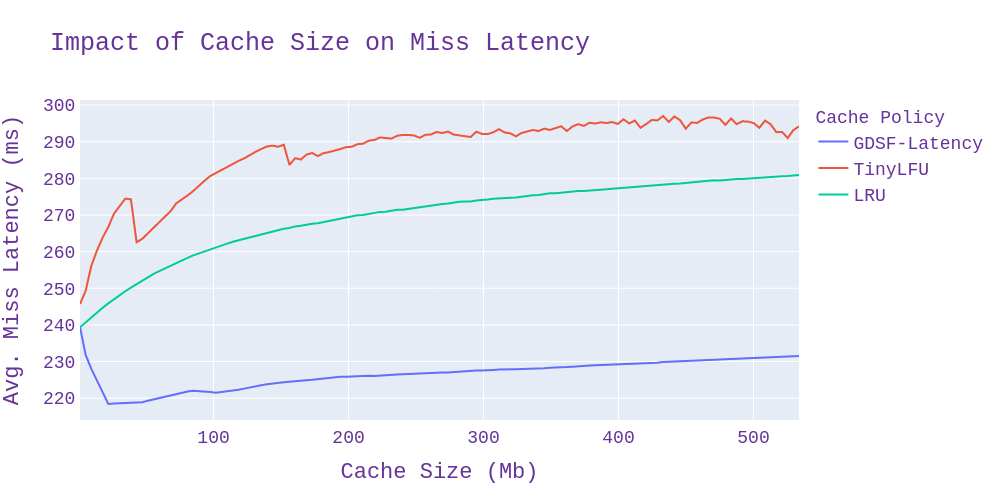

We then ran this benchmark with multiple cache sizes against the three caching schemes provided with Cachemere: LRU, TinyLFU, and GDSF and measured the hit rate as well as the average latency per cache access.

From the characteristics of each caching scheme described above, we expect both GDSF and TinyLFU to have a considerable edge over LRU in all benchmarks. We also expect TinyLFU to be ahead in hit rate benchmarks, while GDSF should come out on top in the cost (latency) benchmark.

For the hit rate, the results are very straightforward. Both TinyLFU and GDSF significantly outperform LRU for all tested cache sizes, with TinyLFU coming out ahead, as expected.

As for average latency, the results are initially a bit more surprising. GDSF performs very well - as expected - but TinyLFU seems to be performing much better than anticipated considering that it pays no attention whatsoever to cost of cache misses. Upon further examination however, this result is explained by the fact that TinyLFU has a higher overall hit rate, so the average cost ends up lower even though no effort is made to minimize reload cost.

We can confirm this by plotting the average reload cost on cache miss instead of overall, and doing so makes it clear that GDSF does a pretty good job of reducing latency.

It is also worth noting that TinyLFU has a higher average miss latency than LRU because maximizing hit rate has the side effect of heavily prioritizing small items, meaning that the larger and more expensive items are often left out of the cache.

With these results, we can be confident that Cachemere offers tools that are good enough to improve the performance of our caches while uniting all of them under a single implementation.

Next Steps

We are now at the stage of progressively replacing caches in the Coveo index with Cachemere’s offering, starting with the simplest caches and working our way up towards the most complex ones. Along the way we’ll certainly be making exciting additions to the library, focusing at first on performance.

Cachemere still being in its early days, be sure to let us know how it works (or doesn’t work) for you if you do give it a try. We’re also open to contributions, so feel free to get in touch!

Do you like this type of challenge? Do you think there are other ways to improve our caches? Join the Coveo Team and help us improve the search experience!