In October 2017, Salesforce released Salesforce DX. It brought source-driven development and scratch orgs to the Salesforce developer community, a considerable boon for every Salesforce developer. However, when creating a package, the source of truth was still the code that lived in the packaging organization, and not the code that was in your repository.

2 years later, October 2019, Second-Generation Managed Package became GA, bringing the source-driven development to the packaging. This unified the code in a single place: your repository.

Such shifts in the development process might seem daunting at first, but let me show you how you could organize your code with those tools, and what it will bring to you and your users.

Preamble

- Most of the following content can be applied to managed package development for ISV, but you might find some practices and ideas that can apply to your workflow nonetheless.

- The semantic used in this document does not necessarily reflect the official Salesforce lexicon. Don’t use it as a reference.

- The source code of the example project used in this blogpost is available on this GitHub repository.

Phase 0: MDAPI Project

The MDAPI file structure is how files have been structured for a long time in Salesforce. Those files are sometimes bulky and hard to collaborate on. This is why the Source Format was introduced with Salesforce DX. If your project is still structured around the MDAPI format, switching to the source format might save you numerous bad merge and headaches Here are some resources to help you structuring your project:

- Salesforce DX Project Structure and Source Format, explains what is the Source Format.

- SDFX-CLI, mdapi Commands, some useful commands to work with your MDAPI files (

force:mdapi:convertwill be the one you want to check out to convert your repository).

Phase 1: A monolithic package with a monolithic package directory structure

A ‘monolithic package’ is a single Salesforce package containing the integrality of your product. A monolithic directory is constituted of a single package directory (a directory containing for example an lwc or object folder).

It contains all the files related to your package in a single folder.

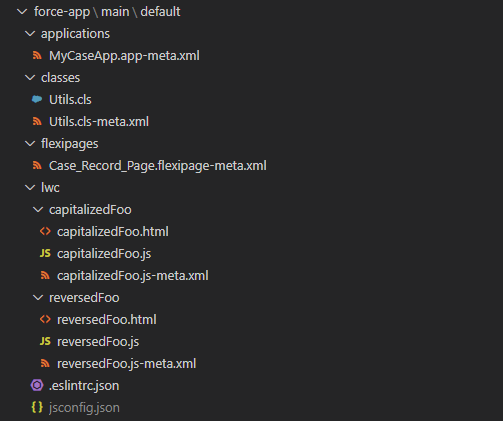

For example, here’s what a simple project with a simple console application with a layout and some Lightning Web Components (a.k.a. LWC) would look like:

Pros

- It’s simple.

- It’s close to the MDAPI file structure (it’d be what you get from a

sfdx force:mdapi:convertrun even).

Cons

- It’s not scalable if you start getting a lot of features: If you have two distinct feature sets, you might want to split your files between those two, but you won’t be able to do so, because the subfolders under your package directory are expecting files matching their names (so, LWC bundles in the

lwcfolder and Aura bundles inaurafolder. However, because of the subfolder restrictions, you cannot bundle LWC in a subfolder like this:lwc/subfolder/myComponent). - You have a single big package, which can be cumbersome for your users (e.g. they might want less static resources).

First-Generation Managed package:

You should check the First-Generation Managed Packages documentation from the Salesforce DX Developer Guide which goes in detail on how to deploy a managed 1st Gen package from the source format.

Second-Generation Managed Packages:

You should check the Second-Generation Managed Package documentation from the Salesforce DX Developer Guide which explains the release and publishing process of a 2nd Gen package.

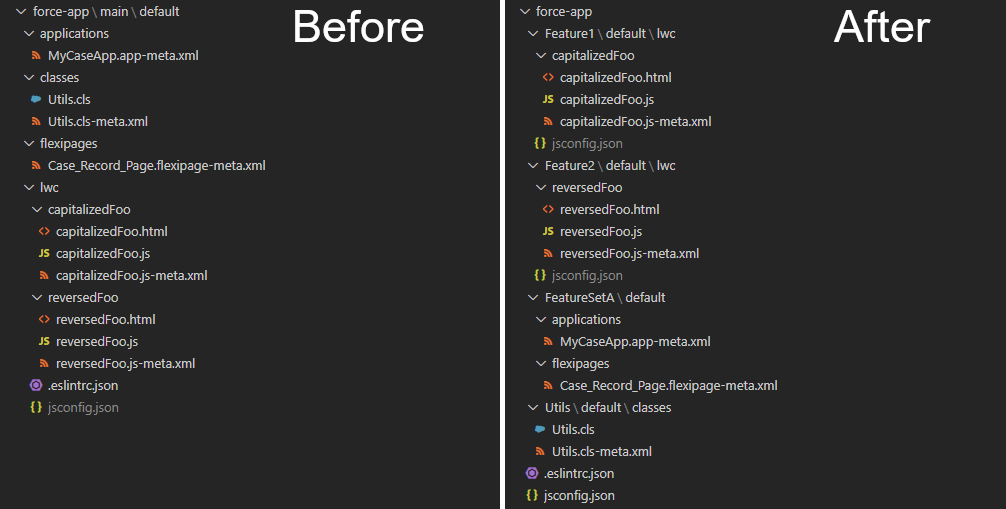

Phase 2: Monolithic managed package and feature-oriented directory structure.

A feature-oriented directory structure applies the Separation of Concerns design principle to the directory structure of your SalesforceDX project. It splits the files in different folders depending on their “raison d’être”, meaning that if two components/classes have no relations between them, they should certainly be split in different folders.

For example, if you have some LWCs for Salesforce Community and others for Salesforce Lightning Console, chances are they should not be in the same folder.

If they have some shared code/logic, it could be split in a ‘util’ directory. Also, you can make multiple util directories. However, you should also apply the Separation of Concerns principle to those too.

So if we take the example from the Phase 1, it could be changed to a structure like this:

For this phase, the sfdx-project.json should stay the same and target the force-app folder as a whole:

{

"packageDirectories": [

{

"path": "force-app",

"default": true

}

],

"namespace": "",

"sfdcLoginUrl": "https://login.salesforce.com",

"sourceApiVersion": "48.0"

}

Even with the files distributed among different folders, the Salesforce-CLI stitches them together as one in the end. Thanks to that, when using sfdx force:source:push or publishing the package, the result will still be the same as in Phase 1.

Pros

- The development is scalable. As a developer, this should prevent you from getting lost in your files.

- It should better represent what the client cares about and the different ‘solutions’ included in your package.

- It can be used with 1st or 2nd Generation Packaging

Cons

- It’s quite different from the MDAPI file structure, so you might get confused at first if you’re used to the latter.

- What you ship and your code are different, which is something to keep in mind.

- You still have a single big package, which can be cumbersome for your users (e.g. they’ll surely still want less static resources).

- You might still be using the First Generation Packaging and thus missing on some goodness of the Second!

Phase 3: Monolithic Second Generation Managed Package and feature-oriented directory structure.

If you are already using the Second Generation Packaging, there’s nothing new between Phase 2 and this one.

If not, this phase would mostly be the migration from the First Generation Packaging to the Second. However, not much information has been shared on the topic yet apart for an upcoming developer preview.

From there, we’re assuming that you’re using a 2GP.

Pros

- Same as Phase 2, but also:

- It’s using the Second Generation Packaging, which allows way more flexible and simpler package creation (see Comparison of 2GP and 1GP Managed Packages)

- Your source code is what you ship 🎉!

Cons

- You still have a single big package, which can be cumbersome for your users (e.g. by now, they might starting getting a bit vocal about it…).

Phase 4: Feature-oriented Second Generation Managed Packages and directory structure.

Finally, to ease the installation burden of your user, you can split your packages into smaller ones.

The directories created on phase 2 must now be defined as packages in the sfdx-project.json.

Those packages must explicitly specify their dependencies in the sfdx-project.json.

You should create ‘empty’ packages (later called ‘feature set package’) that group your features per use cases. For example, if one of your personas is supposed to use multiple independent lightning components to have the best experience with one of your feature set, you should:

- Split each of these independent lightning components in their own package.

- Have an empty package that defines those packages as a dependency. Do not neglect the scope and name of this package, they still need to be ‘focused’ on a specific use case (e.g. for Coveo for Salesforce, one such package could be the Service Cloud Package or the Commerce Cloud Package).

That does not mean that you should have one package per component, but instead that you should ask yourself “Can my component be used as a standalone?”.

If the answer is yes, you may want to have a single package for it.

You can also add a ‘demo’ showing how to use them. For example in the case of a record page, you could include a flexipage with your components properly setup.

For backward compatibility, you should create a main package that specifies all the feature set packages as dependencies.

The

.placeholderfile is just there to ensure Git does commit the folder, you must also add it to your.forceignorefile so that Salesforce CLI ignores it when pushing code.

In the end, with our example, it would look like this:

{

"packageDirectories": [

{

"path": "force-app",

"default": true

},

{

"package": "Main",

"versionNumber": "0.0.0.NEXT",

"path": "force-app/main/",

"default": false

},

{

"package": "FeatureSetA",

"versionNumber": "0.0.0.NEXT",

"path": "force-app/FeatureSetA/",

"default": false,

"dependencies": [

{

"package": "Feature1",

"versionNumber": "0.0.0.LATEST"

},

{

"package": "Feature2",

"versionNumber": "0.0.0.LATEST"

}

]

},

{

"package": "Feature1",

"versionNumber": "0.0.0.NEXT",

"path": "force-app/Feature1/",

"default": false,

"dependencies": [

{

"package": "Utils",

"versionNumber": "0.0.0.LATEST"

}

]

},

{

"package": "Feature2",

"versionNumber": "0.0.0.NEXT",

"path": "force-app/Feature2/",

"default": false,

"dependencies": [

{

"package": "Utils",

"versionNumber": "0.0.0.LATEST"

}

]

},

{

"package": "Utils",

"versionNumber": "0.0.0.NEXT",

"path": "force-app/Utils/",

"default": false

}

],

"namespace": "",

"sfdcLoginUrl": "https://login.salesforce.com",

"sourceApiVersion": "48.0",

"packageAliases": {

"Main":"04tB00000000000",

"FeatureSetA":"04tB00000000001",

"Feature1":"04tB00000000002",

"Feature2":"04tB00000000003",

"Utils":"04tB00000000004"

}

}

Pros

- You ship smaller, self-contained features. That should allow better scalability, for the product and for your team. (i.e. more people can work on your project, and it can contain more stuff).

- Your client can reduce their installation size by installing only what they need.

- Newcomers to the project can onboard more easily because they don’t need to understand the ‘broad picture’ of the whole project but instead a reduced subset of it.

Cons

- You have a lot of different packages. You must stay vigilant, or your project will become a mess.

TL;DR and tips:

- Use the Source Format today, if you don’t already.

- Use it smartly. Future You will thank you for splitting and structuring your code today.

- Baby steps, do it progressively. The phases are more like milestones, meaning that, at least for the file structure, you can be in-between two phases, with a ‘historic’ folder for what existed before you decided to use the feature-oriented file structure. And then, when developing new features, refactor their dependencies.