If you work for any given amount of time as a software developer, one problem you’ll end up with is parsing structured text to extract meaningful information.

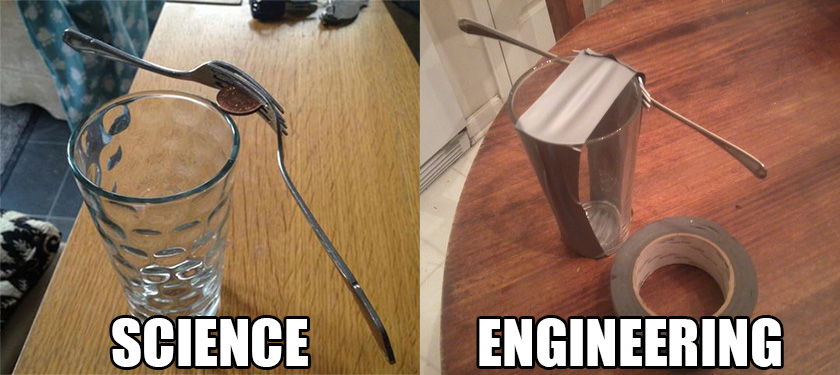

I’ve faced this issue more than I care to remember. I even think that’s why I learned regular expressions in the first place. But, as Internet wisdom will teach you regexes are only suitable for a subset of the parsing problems out there. We learn it at school: grammars are the way to go. Still, it is my deep belief that most engineers, when faced with a parsing problem, will first try to weasel their way out using regular expressions. Why? Well…

(do try that trick with the forks, it’s awesome)

There are many tools you can use to generate parsers in various languages. Most of those involve running some custom compilation step over your grammar file, from which a set of source code files will be produced. You’ll have to include those in your build, and then figure out a way to use them to transform your input text into a meaningful structure. Hmm. Better go fetch the duct tape.

Enter parser combinators. As Wikipedia states, parser combinators are essentially a way of combining higher order functions recognizing simple inputs to create functions recognizing more complex input. It might all sound complex and theoric, but it’s in fact pretty simple. Here’s an example: suppose I have two functions able to recognize the ( and ) tokens in some text input. Using parser combinators, I could assemble those to recognize a sequence in that input made up of an opening parens and then a closing one (of course in the real world you’d want stuff in between too).

Still too complex? Let’s see some real world code now. Let’s implement a simple parser for performing additions and subtractions (ex: 1 + 2 + (3 + 4) + 5). I’ll use Scala because it’s base library comes with built-in support for parser combinators, but similar functionality is available for other languages too.

First, let’s define a few classes to hold our AST:

abstract class Expression {

def evaluate(): Int

}

case class Number(value: Int) extends Expression {

def evaluate() = value

}

case class Parens(expression: Expression) extends Expression {

def evaluate() = expression.evaluate()

}

case class Addition(left: Expression, right: Expression) extends Expression {

def evaluate() = left.evaluate() + right.evaluate()

}

case class Substraction(left: Expression, right: Expression) extends Expression {

def evaluate() = left.evaluate() - right.evaluate()

}For the curious, a case class in Scala is essentially a shorthand for immutable classes holding a few properties. They automatically come with an proper equals and toString implementation (among other things). They are perfect for this purpose.

Now here’s the parser that goes with it:

object SimpleExpressionParser extends RegexParsers {

def parse(s: String): Expression = {

parseAll(expression, s) match {

case Success(r, _) => r

case NoSuccess(msg, _) => throw new Exception(msg)

}

}

val expression: Parser[Expression] = binary | parens | number

val parens = "(" ~ expression ~ ")" ^^ {

case "(" ~ e ~ ")" => Parens(e)

}

val binary = (number | parens) ~ operator ~ expression ^^ {

case l ~ "+" ~ r => Addition(l, r)

case l ~ "-" ~ r => Substraction(l, r)

}

val number = regex( """\d+""".r) ^^ {

case v => Number(v.toInt)

}

val operator = "+" | "-"

}The parser is in fact a class (in this case a Singleton but that’s not mandatory). It’s methods define a set of rules that can be used for parsing. Notice how close those look to a typical BNF grammar? That’s right, you won’t be needing that duct tape after all.

Rules can be very simple such as operator which recognizes simple tokens using either strings or regular expressions, or more complex such as binary which combines other rules using special operators. Note that those operators are just methods from the base RegexParsers class. The Scala libraries provide many operators and methods to define how parsers can be combined. In this case I’m using the ~ operator which denotes a sequence. It’s also possible to match variable sequences, optional values, and many, many others.

The return value for each rule is in fact a Parser[T] where T is the type of item that is recognized. Simple rules based on strings or regular expressions return a Parser[String] without the need for further processing. Rules that combine multiple values or that need the raw token to be transformed in some way (such as number) can be followed by the ˆˆ operator applied to a partial function that’ll match the recognized stuff using pattern matching and then produce the resulting value. For example, binary returns either an Addition or a Substraction, which means it’s inferred return value is Parser[Expression].

Here’s how this parser could be used:

assertEquals(1, SimpleExpressionParser.parse("1").evaluate())

assertEquals(3, SimpleExpressionParser.parse("1 + 2").evaluate())

assertEquals(15, SimpleExpressionParser.parse("1 + (2 + 3) + 4 + 5").evaluate())The parse method either returns an Expression or throws an exception when a parsing error occurs. Then calling evaluate on that expression recursively computes the expression, and returns the result.

If I were to use the toString method on the root expression, for an input string 1 + 2 I would end up with Addition(Number(1),Number(2)), which shows that the result from the parsing is a nice, easy to use AST.

Dealing with left recursive grammars

You might have noticed that in my example the definition for the binary rule didn’t use expression on the left side of the operator. Why can’t I do something like this?

def binary = expression ~ operator ~ expressionThe problem with this rule is that is makes my grammar a left recursive one, and by default the Scala parser combinators don’t handle that quite well. While processing the input, the expression rule is then called, which eventually digs into binary, which then invokes expression again on the same input … and then you end up with (and on) Stack Overflow.

So how to work around this? One possibility is to ensure that your grammar never recurses to the same rule without consuming at least one character (e.g. do not use left-recursion). That’s why I used a slightly more complex form in my initial sample. Another possibility when using Scala parser combinators is to mix in the PackratParser trait into your class, which enables support for left-recursion:

object SimpleExpressionParser extends RegexParsers with PackratParsers {

def parse(s: String): Expression = {

parseAll(expression, s) match {

case Success(r, _) => r

case NoSuccess(msg, _) => throw new Exception(msg)

}

}

val expression: PackratParser[Expression] = binary | parens | number

val parens = "(" ~ expression ~ ")" ^^ {

case "(" ~ e ~ ")" => Parens(e)

}

val binary = expression ~ operator ~ expression ^^ {

case l ~ "+" ~ r => Addition(l, r)

case l ~ "-" ~ r => Substraction(l, r)

}

val number = regex( """\d+""".r) ^^ {

case v => Number(v.toInt)

}

val operator = "+" | "-"

}Much better isn’t it?

Conclusion

In this post I’ve only shown a very simple parser, but using the same techniques it’s possible to build much more complex ones that can process just about any kind of structured expression, without the need for external tools, and using very little code. All of sudden, recognizing complex expressions no longer becomes an issue, and this opens up many possibilities when faced with situations where custom text input is being used. So give it a try!